ALERT!

This site is not optimized for Internet Explorer 8 (or older).

Please upgrade to a newer version of Internet Explorer or use an alternate browser such as Chrome or Firefox.

Laparoscopic Repair of Giant Paraesophageal Hernias

Patient Selection

|

| Figure 1. Barium swallow |

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is extremely common in North America. The majority of these patients will have a simple type I hiatus hernia. The approach to this repair is usually by laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Much less frequently patients will present with a giant paraesophageal hernia (GPEH) (Figure 1). This type of hernia likely results from progression of a simple type I hernia with rolling of the fundus up alongside the gastroesophageal junction. Most patients are symptomatic, with dysphagia and heartburn being extremely common problems (Table 1). Rarely are patients truly asymptomatic. There are no absolute contraindications to the use of the laparoscopic approach.

| Table 1. Preoperative Symptoms and Findings from 203 Patients | |

|---|---|

| Typical Heartburn | 47 |

| Dysphagia | 35 |

| Epigastric Pain | 26 |

| Vomiting | 23 |

| Anemia | 21 |

| Barrett's Epithelium | 13 |

| Aspiration | 7 |

Many controversies have existed about repair of these GPEHs. We feel that all symptomatic patients should be repaired to relieve symptoms and to prevent future complications. Asymptomatic patients can be followed carefully and should be operated on if symptoms develop. We also favor an antireflux repair for these cases in association with an esophageal lengthening procedure (Collis gastroplasty).

Traditionally, repair of GPEHs has been performed through an open laparotomy or left thoracotomy. With the advent of laparoscopy, GPEHs are now being approached with minimally invasive techniques. Less invasive procedures may decrease the amount of postoperative pain and the perioperative complication rate, and shorten recovery time.

The patient's preoperative evaluation includes a barium esophagram and upper endoscopy. A 24-hour esophageal pH study and/or esophageal manometry is obtained in some cases. It may be difficult or dangerous to instrument the esophagus so pH or manometry studies are frequently omitted. Endoscopy is usually performed at the time of surgery. If it is difficult to enter the stomach the scope is left in the esophagus until after the stomach has been reduced back into the abdomen. It is then easy to perform intraoperative endoscopy to evaluate the esophagus and stomach for pathology before proceeding with the repair.

Operative Steps

|

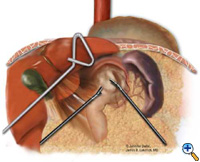

| Figure 2: Laparoscopic port-site placement for repair of giant paraesophageal hernia. |

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table, and the surgeon works from the right side with the assistant on the left. Four 5 mm and one 10 mm laparoscopic ports (Versaport, United States Surgical Corporation (USSC); Norwalk, CT) are placed in the upper abdomen (Figure 2). The left lateral segment of the liver is retracted anteriorly with a 5 mm flexible retractor (Snowden Pencer, Genzyme; Tucker, GA) and secured to a stationary holding device (Mediflex; Islanda, NY).

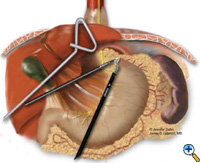

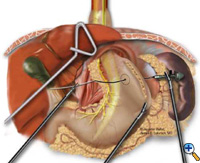

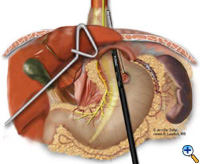

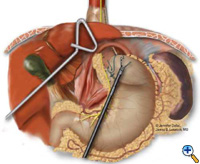

After exposing the hiatus, the herniated stomach is reduced into the abdomen using atraumatic graspers (Snowden Pencer) in a "hand-over-hand" fashion (Figure 3). Dissection is started by dividing the gastrohepatic ligament and exposing the right crus of the diaphragm using the ultrasonic shears (USSC) or the harmonic scalpel (Ethicon; Cincinnati, OH). Next, the gastrosplenic ligament is divided along with the posterior attachments to the fundus. Dissection is continued to expose the junction of the right and left crura at the retroesophageal space. The hernia sac and the gastroesophageal fat pad are carefully dissected out, sweeping the anterior vagus nerve to the right of the esophagus with the fat pad (Figure 4). A combination of sharp dissection with the ultrasonic shears and blunt dissection with graspers is used to completely remove the hernia sac from the mediastinum and away from the area of the diaphragmatic repair or the fundoplication. The entire sac should be removed from the hernia cavity, parts of the sac may be left in proximity to the vagus nerves to avoid injury. The distal esophagus is then mobilized superiorly to determine whether esophageal shortening is present.

|

|

|

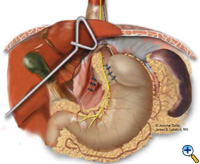

| Figure 3: Laparoscopic "hand-over-hand" reduction of intrathoracic stomach. | Figure 4: Dissection of anterior gastroesophageal fat pad. | Figure 5: Anvil positioning for EEA stapler. |

If the esophagogastric junction does not remain below the diaphragmatic hiatus with an adequate, tension-free segment of intraabdominal esophagus, a Collis gastroplasty is added before fundoplication. A Maloney esophageal bougie is placed transorally by the surgical team across the gastroesophageal junction along the lesser curve. We typically use a 50 French bougie. A large tapered needle attached to a #2 Vicryl suture is straightened and tied to the point of the anvil of the 21 mm EEA stapler (USSC), and the needle is passed through the stomach from posterior to anterior adjacent to the bougie (Figure 5) approximately 4-5 cm distal to the level of the gastroesophageal junction. The anvil is then pulled gently through the posterior and anterior stomach walls adjacent to the bougie. Judicious application of the electrocautery facilitates passage of the anvil tip. The EEA stapler is then inserted into the abdomen, joined to the anvil, and then fired. The fired EEA stapler creates a circular defect in the stomach wall that allows completion of the gastroplasty segment with the endo-GIA stapler. The endo-GIA II (USSC) is fired in a cranial direction, snugly against the bougie, to create at least 4 cm of tension-free intraabdominal neoesophagus (Figure 6).

|

|

|

| Figure 6: Creation of neoesophagus with Endo-GIA stapler. | Figure 7: Suturing of 360 degree wrap around Collis segment. | Figure 8: Completed crural repair and Collis-Nissen fundoplication. |

The esophagus or neoesophagus is wrapped with the mobilized gastric fundus in a 2-3 cm floppy Nissen fundoplication over a bougie. Typically, 3 interrupted sutures (2-0 Surgidac, Endostitch, USSC) are used for the fundoplication (Figure 7). The bougie is then removed and a nasogastric tube inserted. The crura are approximated posteriorly with interrupted 0 braided polyester suture (Surgidac, USSC) again using the Endostitch device (USSC) (Figure 8). In most cases the crura are approximated primarily without excess tension. In unusual cases of an excessively large defect, a patch of Gore-Tex (W.L. Gore; Flagstaff, AZ) is used to reinforce the closure.

The nasogastric tube is removed on postoperative day one and a barium swallow is obtained to evaluate the repair and rule out a leak. If no leak is found then clear liquids are started that day, and the patient is discharged home on postoperative day 2. The diet is advanced at home to a regular diet over the subsequent 3 weeks. All patients are seen in follow-up at 1 month with another barium swallow.

Preference Card

- Ultrasonic Shears (AutoSonix, USSC)

- Self-retaining liver retractor (Diamond Flexible Liver Retractor, Snowden-Pencer)

- Atraumatic tissue graspers (Diamond touch crocodile 5mm, Snowden-Pencer)

- Standard EEA stapler and Endo-GIA II

- Endo-stitch

Tips & Pitfalls

- Ports need to be placed high on the abdomen since much of the stomach will be up in the mediastinum.

- Use both compression stockings and subcutaneous heparin to prevent deep venous thrombosis.

- Attempt to work at intraabdominal pressures less than 15 mmHg if possible.

- We prefer the fine tip of the ultrasonic shears for mobilization of the anterior gastroesophageal fat pad.

- It is important to remove the hernia sac from the mediastinum while avoiding entry into the pleural spaces.

- Handle the stomach gently with graspers - the chronically herniated stomach perforates relatively easily!

- Watch carefully for perforations or leaks during dissection.

- When evaluating esophageal length keep in mind that a bougie often pushes the esophagus down and that pneumoperitoneum elevates the diaphragm giving a false sense of intraabdominal esophageal length. The use of a penrose drain with downward tension may also give the surgeon a false impression of adequate length.

- We now use a Collis gastroplasty for all giant paraesophageal hernias.

- Examine the staple-lines of the Collis gastroplasty carefully for integrity and leaks.

- Intracorporeal suture techniques are essential and can be easily learned with inanimate training models or advanced courses in laparoscopy.

- Perform intraoperative endoscopy to look for leaks if necessary.

- Pass the bougie yourself, and always communicate with anyone placing objects in the esophagus by mouth.

- Mesh is rarely needed if the diaphragm is mobilized appropriately.

- Convert to open if necessary - conversion is not a complication.

- Extensive open esophageal surgical experience and laparoscopic experience with routine Nissen repairs are pre-requisites for this complicated surgery.

- Strong consideration should be given to specialized training in advanced minimally invasive surgery before embarking on this complex repair.

Results

We have now performed laparoscopic repair of giant paraesophageal hernia in over 200 cases at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. The median operative time was 3.3 hours. The postoperative esophageal leak rate was 3% and the moratality rate was only 0.5%. Median follow-up was 18 months. Excellent results were reported in 84% of patients, 8% had a good result, 5% fair, and 3% poor (based on GERD-HRQOL score). Overall, 93% of patients were "satisfied" with their result at the time of the follow-up. Postoperatively, 6% had dysphagia requiring dilation, and 2.5% of patients required reoperation for recurrent hiatal hernia.

References

- Skinner DB, Belsey RH. Surgical management of esophageal reflux and hiatus hernia: long-term results with 1,030 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1967;53:33-54.

- Allen MS, Trastek VF, Deschamps C, Pairolero PC. Intrathoracic stomach. Presentation and results of operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993;105:253-59.

- Maziak DE, Todd TR, Pearson FG. Massive hiatus hernia: evaluation and surgical management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;115:53-60.

- Luketich JD, Raja S, Fernando HC, et al. Laparoscopic repair of giant paraesophageal hernia: 100 consecutive cases. Ann Surg 2000;232:608-18.

- Wiechmann RJ, Ferguson MK, Naunheim KS, et al. Laparoscopic management of giant paraesophageal herniation. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;71:1080-87.

- Dahlberg PS, Deschamps C, Miller DL, Allen MS, Nichols FC, Pairolero PC. Laparoscopic repair of large paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:1125-29.

- Pierre AF, Luketich JD, Fernando HC, et al. Results of laparoscopic repair of giant paraesopahgeal hernias: 200 consecutive cases. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:1909-16.