ALERT!

This site is not optimized for Internet Explorer 8 (or older).

Please upgrade to a newer version of Internet Explorer or use an alternate browser such as Chrome or Firefox.

How to help your patients stop smoking. A guide for surgeons

Index

Patient Selection

Since a substantial number of patients presenting to a Cardiothoracic Surgery Clinic either smoked in the recent past or continue to do so, it is important to make sure that the patient stops smoking as soon as possible to improve their treatment outcome. The emphasis should be on improvement of treatment outcome and future health improvement. Reinforcing the guilt feelings the patient may already have is counterproductive, and is a significant concern of patient and patient advocacy groups at the present time.

There are evidence-based guidelines regarding smoking cessation techniques that have resulted from reviews of the world’s literature, have been updated, and are very well accepted throughout the medical and psychological fields. The United States is updating its guidelines in spring 2008. The biggest problem is routine implementation by healthcare providers. While most emphasis has been in the primary care setting, specialists deal with the health problems resulting from the smoking as the patient faces imminent surgery. Since ongoing smoking may significantly impair treatment outcomes and survival, it is prudent for specialist to provide urgent smoking cessation treatment.

|

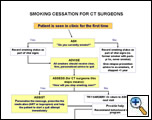

| Figure 1: Algorithm for helping patients quit smoking based on the 5 A’s |

Smoking cessation advice includes the '5 A’s':

ASK

ADVISE

ASSESS

ASSIST

ARRANGE

An even simpler algorithm is ASK, ADVISE and REFER. But, first, the basics will be covered:

The most important step is the first one – ASK the patient about smoking behavior. It has been recommended that smoking or tobacco use should be as fundamental to the history as vital signs are to the physical examination. Tobacco use can be assessed with a check-in questionnaire, but it needs to be reviewed by the surgeon.

Sample questions are listed below that provide a comprehensive smoking history and would be most appropriate for either a questionnaire while the patient is waiting to see the surgeon or perhaps should be asked by the nurse. Given the paucity of prospective data on smoking status in clinical trials in smoking related diseases, whether oncological or cardiovascular, such a questionnaire would provide valuable data on future outcome measures. These questions have been adapted from the National Health Interview Survey and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey and should provide uniformity between datasets [1].

IF THE PATIENT IS STILL SMOKING/USING TOBACCO:

The discussion of quitting should be part of the first visit. The surgeon should utilize this first visit as the 'teachable moment' to emphasize or 'personalize' the importance and urgency of quitting. The surgeon must understand that nicotine addiction is one of the most difficult addictions to overcome and most patients have tried many times to quit. Despite the stress involved in contemplating surgery or the diagnosis of cancer, most patients will understand that quitting smoking is one of the most important contributions that THEY can currently bring to their therapy and it is required of them at this point. If the surgeon presents such a strong recommendation, the patient will often listen.

Thus, the ADVISE step is readily incorporated into the treatment plan. It is a perfect time to recommend to patients that they have already stopped smoking – that the last cigarette they had before arrival at the clinic/hospital should be their last cigarette. Continued tobacco use is likely to adversely affect treatment delivery, short-term outcomes, and long-term results. The patients should see themselves as partners with the healthcare team in achieving the best possible results. The most important part of the patient’s participation in their treatment plan is to stop smoking – NOW. Setting a quit date in the future is not an option for the patient with imminent surgery. The patient should understand that psychologically, continued smoking after a decision in the physician’s office to stop makes it more difficult to quit because of the severe addiction caused by nicotine. Basically, the patient needs to understand that the quit needs to occur immediately – or perhaps upon awakening the next morning. This timing actually facilitates the treatment planning, and relays the urgency to the patient.

Standard smoking cessation advice counseling instructions usually suggest that the physician assess the patient’s ‘readiness’ to quit’ – the 'ASSESS' step. The surgeon could argue that when the patient is imminently facing either cardiac or thoracic surgery with or without neo/neoadjuvant therapy - that this requires the patient to quit NOW. The patient is past the point of ‘contemplating’ quitting and they must do it now.

Supportive methodologies to ASSIST with the quitting process must also be discussed with the patient. 'Cold turkey' – or without any support is NOT the most successful way to quit smoking. That being said, most people who quit, do quit ‘cold turkey’. USA smoking cessation guidelines recommend three different first line forms of pharmacotherapy: either nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion (Zyban) or the newest drug, varenicline (Chantix-USA or Champix-rest of world). Each of these therapies alone approximately doubles the Odds Ratios for quitting over placebo quit rates. The surgeon or nurse should ask the patient which they would prefer or which they have tried – they probably have experience with at least one of them. In addition, the one basic question that the surgeon keeps in their repertoire for smoking cessation is: 'How long after you get up do you have your first cigarette?' If it is within 30 minutes, they should be considered heavily addicted, and if it is longer than 30 minutes, they are less addicted. This will help to guide the dosing of the nicotine replacement therapy.

TABLE 1: AIDS TO SMOKING CESSATION

|

Name |

Side Effects |

Precautions |

Dose |

Duration |

Rx or OTC |

|

Nicotine gum |

Mouth soreness; hiccups/ dyspepsia |

Dentures |

Heavier smoker: 4 mg Lighter smoker: 2mg 1-2/hr; Up to 24/day |

Wean off by 6 months;12 months at latest |

OTC |

|

Nicotine lozenge |

Hiccups/ dyspepsia |

|

Heavier smoker: 4 mg Lighter smoker: 2mg 1-2/hr; Up to 24/day |

Wean off by 6 months;12 months at latest |

OTC |

|

*Nicotine sublingual (where sold) |

|

|

*2mg lozenge take 1 or 2/hr depending on light or heavy smoker up to 40/day |

Wean off by 6 months;12 months at latest |

OTC (if available – outside US) |

|

Nicotine inhalator |

Irritation of buccal mucosa and throat |

|

6-16 cartridges/day |

Wean off by 6 months;12 months at latest |

Rx in the US; OTC elsewhere |

|

Nicotine nasal spray |

Nasal irritation |

|

8-40 doses/day |

Wean off by 6 months;12 months at latest |

Rx |

|

Nicotine patch |

Local skin reaction Insomnia |

Sensitive skin |

21 mg} 6 wk 14 mg} 2 wk 7 mg} 2 wk or 15 mg 8wk

|

Duration is as some manufacturers recommend, but studies have not demonstrated efficacy with duration longer than 8 weeks. |

OTC |

|

Bupropion SR |

Insomnia, dry mouth |

Hx of seizure or eating disorders |

150 mg q AM x 3 days then 150 mg BID |

7-12 wks; or up to 1 year |

Rx |

| Varenicline | Nausea | 0.5 mg AMx3 days; 0.5 mg BIDx3days; 1 mg BID | 12 weeks; can extend another 12 weeks | Rx |

*currently not available in the USA, if/when available, side effects, precautions and dosing may need to be revised.

Nicotine replacement therapies

Nicotine Gum (2 or 4 mg) has been on the market the longest, is non-prescription, and is used in doses of 2 mg for 'lighter ' (<24 cpd) or 4 mg for 'heavier' (>24 cpd) smokers. This is fairly unrealistic labeling, however, as the average US smoker today consumes about 17 cpd and by other addictiveness scales they are fairly heavily addicted, suggesting that 4 mg is more appropriate initially for most US smokers. Studies show that many people quitting smoking with gum don’t use enough gum per day to adequately relieve their cravings. So, it is important to tell people to use enough pieces (at least 9) per day to relieve their cravings.

The nicotine lozenge also comes in 2 or 4 mg strengths but is differentiated according to the time of day that the smoker has their first cigarette. Most US smokers have their first cigarette within 30 minutes (more 'heavily addicted') and therefore should use the 4 mg lozenge. A reasonable suggestion is for the smoker to purchase the smallest box of either the gum or the lozenge, make sure that they can tolerate the 4 mg dose and that they WILL use it, and then purchase the subsequent boxes in the larger sizes that may be more cost efficient. Again, it is important that sufficient pieces of lozenge (or gum) are used per day to relieve cravings to prevent relapse to smoking, particularly early in the quitting period.

The 'inhaler' or inhalator is a buccally delivered product that still requires a prescription in the US, though usually not elsewhere in the world. As with the other buccally delivered products, it delivers a maximum of 4 mg of nicotine, and again, should be used on a frequent enough basis to relieve cravings. It requires sufficient pulmonary function to adequately 'suck' in on the mouthpiece.

The nicotine patch comes in different strengths, depending on the brand. If the smoker has their first cigarette within 30 minutes of awakening they should start on the highest dose (the 21 mg or 15 mg patches in the US). The patches can be worn for 16 or 24 hours. Try recommending that the patch be worn for 24 hours initially to try to prevent the cravings that can occur with awakening. However, the patient can be told that if there are sleep disturbances, the patch can be taken off at bedtime, and a new patch placed first thing in the morning. Patches often do cause skin irritation, so they should be put on a different place every day. The benefit of the patch is that there is not an issue of needing to remember to take sufficient number of doses to ‘relieve cravings’.

Nicotine nasal spray is available by prescription and the patient should be instructed to use one to two sprays (0.5 mg/spray) for a minimum of 8 sprays/day. Initially, the nasal spray may cause some mucosal burning, but this should become more tolerable with use.

In countries other than the USA, a 'microtab' is also available in the 2 mg dose. This is used similarly to the 2 mg lozenge.

Surgeons should be aware that single forms of NRT do not always relieve all cravings. Therefore, patients should be told that they may be able to combine an oral dose form with the patches if they are still having break-through cravings while on the patch. It is better to take a gum, lozenge or dose of the inhalator than a cigarette to relieve a craving. It is very unlikely that the patient will achieve a toxic level of nicotine if they do this to relieve a craving. The usual serum level obtained by the nicotine replacement doses used by quitters is well below their usual nicotine levels from their smoking habit.

Bupropion

Bupropion is a relatively weak inhibitor of the neuronal uptake of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. It has similar efficacy to NRT with a behavioral support program. It is marketed as 150 mg SR (slow release) tablets. Bupropion SR is initiated at 150 mg PO qd for 3 days and then increased to 150 mg PO BID at least 8 hours apart. It should NOT be used in patients with a seizure history or patients with a possible cerebral lesion/metastasis. Smokers are instructed to quit smoking 1 week after starting the bupropion. This is slightly different than the labeled instructions to the nicotine replacement therapy, where they are instructed to quit upon beginning the NRT. NRT may be used in combination with bupropion – it is recommended that the blood pressure be followed as it may be elevated, although it is minimal and infrequent in practice. Again – the problem is getting the quitter to use sufficient NRT to relieve cravings – and NOT return to smoking.

Varenicline (Chantix in the USA; Champix in the rest of world) is a partial nicotine receptor agonist that works most specifically at the alpha4beta2 nicotine receptor. Varenicline diminishes the drug effect of nicotine, thus decreasing the cravings for it. It is patterned off an older herbal drug from eastern Europe, where it has been used for years for smoking cessation. It was approved in many markets, including the USA in 2006. It should be dosed in a similar fashion to bupropion:

Days 1-3: 0.5 mg PO q AM

Days 4-6: 0.5 mg PO BID

Day 7 – quit tobacco

Days 7 onward: 1 mg PO BID

Continue varenicline for 12 weeks; in the USA it is approved for an additional 12 weeks. The drug has been studied for out to one year of use, in order to help prevent relapse. The drug has an excellent safety profile, with adverse events being similar to nicotine: nausea, sleep disturbances and headaches.

Behavioral Support

Even in the 'usual' quitting circumstances that are not linked to an upcoming surgery, the smoker finds quitting extremely difficult. Current guidelines recommend behavior support, which usually increases the success by doubling the odds ratio for quitting. Therefore, even in this pre-operative occurrence, it is best if the surgeon is able to refer the patient to a smoking cessation service that can provide such behavioral support for the patient. In addition, such a clinic or Quitline can further assist with advice concerning whether to add another NRT to the current form of nicotine replacement therapy, or perhaps, adding NRT to bupropion if it is chosen as the first line therapy, or even to switch pharmacotherapy.

When thoracic surgeons work with their patient to stop smoking, they often recommend quitting at least two weeks pre-operatively. Currently, the published data suggests that greater than 2 weeks of cessation is necessary to have a measureable decrease in post-operative complications, such as pneumonia. However, most surgeons are not willing to wait 8-12 weeks that may be recommended from cessation studies. Of course, the longer the period of cessation, the more the body has time to recover from smoking effects. Patients can be asked to quit smoking the day that they are seen in clinic. If surgery is scheduled within 2 weeks, this could affect the choice of pharmacotherapy, as they would need 3 weeks for bupropion or varenicline: 1 week build up, then 2 weeks off of cigarettes. Commonly, the patient’s bronchorrhea decreases after 7-10 days of smoking cessation, and patient’s rarely have post-operative problems from secretions IF THEY QUIT. Patients that do not quit at least 2 weeks prior to surgery may require more intensive post-operative respiratory therapy.

Attention should be paid to the patient’s craving and withdrawal status in the post-operative period. If they did quit 2 weeks pre-operatively, their severe cravings are over, as nicotine has a half-life of 2 hours, and has cleared the body by 24 hours. However, if the patient did not quit pre-operatively, the patient is not only very uncomfortable from just having major surgery but also withdrawing from one of the most addictive drugs known to society – both at the same time. The literature is unclear on the acute of affects on nicotine on the heart – it has not been clinically studied in the immediate post-cardiac-operative period, although often used. Cardiologists have been using NRT in CCUs in acutely withdrawing smokers, but there is a paucity of studies [2,3,4] It is far easier to have the patient stop smoking pre-operatively than to deal with the problem of nicotine withdrawal or its use post-operatively.

The final step – ARRANGE - includes not only the arrangement of the quitting process, but the follow-up and prevention of relapse steps as well. The patient must be discharged home with smoking cessation follow-up instructions – again, preferably to a smoking cessation clinic or quitline. The smoking status – or 'stopped smoking' status - should be confirmed at each follow-up visit and be part of the follow-up note to the referring physician.

Getting the patients to stop smoking or keeping the patient from relapsing to smoking is one of the most important interventions the surgeon can do – it also helps the surgeon to maintain a lower morbidity and mortality rate. In addition, smoking cessation counseling for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure and pneumonia is a Joint Commission (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization) core measure that began with July 2004 discharges [5]. Cessation counseling is also able to be coded for reimbursement

QUITLINES

In the USA, and now many countries, wide access to free-telephone "Quitline" tobacco cessation counseling is available. In the USA, this number is 800-QUIT NOW. This is a tremendous asset to the clinician, as it allows them to simply their patients to cessation counseling. This pathway is called: ASK, ADVISE, REFER. Thus, the first two 'A's' are the same as above: ask the patient about their tobacco use and advise them, with personalization, as to why they should quit. Then, refer them to the Quitline. In the USA, many states have what is called 'fax-referral.' With a fax-referral, the patient and clinic complete a simple questionnaire inquiring how to contact the patient. This is then faxed to the Quitline, and the Quitline staff take it from there. They will call the patient and work with the prescription for cessation pharmacotherapy that the surgeon has prescribed. The Quitline should notify the surgical clinic that the patient was able to be contacted and counseled. Depending on the Quitline, the counseling is either short and simple, or longer and more supportive. Each surgeon should find out if this service is available to them – and if it isn’t, they should encourage their Quitline to provide the service. Often, the patient’s insurance company also provides smoking cessation counseling: each clinic should determine what is available in their area and for their patients. There is a very significant amount of counseling support available already out there, whether in group sessions, telephone quitlines or web-based cessation support. Most importantly, the surgeon should initiate the process by Ask, Advise (and write the prescription) and Refer.

Appendix 1: Questions for Tobacco Use Assessment

Quick Reading List:

www.treatobacco.net - an evidence-based site containing information in 11 languages on tobacco dependence treatment relative to: efficacy, safety, demographics and health effects, health economics, and policy.

Re: guidelines: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/ or

http://www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=2958&nbr=2184

Re: everything you wanted to know about tobacco at the CDC: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/

References

1. Gritz ER, Dresler CM, Sarna L. Smoking: the missing drug interaction in oncology clinical trials OR ignoring the obvious. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2005;14:2287-93.

2. Zevin S, Jacob P, Benowitz NL. Dose-related cardiovascular and endocrine effects of transdermal nicotine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1998;64:87-9

3. Mahmarian JJ, Moye LA, Nasser GA, et al. Nicotine patch therapy in smoking cessation reduces the extent of exercise-induced myocardial ischemia. J AM Coll Cardiol 1997;30:135-130.

4. Zevin S, Benowitz NL. Drug interactions with tobacco smoking. An update. Clin Pharmacokinet 1999;36:425-38.

5. Specification Manual for National Implementation of Hospital Core Measures Version 2.0: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization http://www.jcaho.org/pms/core+measures/information+on+final+specifications.htm accessed 8 June 2005.