ALERT!

This site is not optimized for Internet Explorer 8 (or older).

Please upgrade to a newer version of Internet Explorer or use an alternate browser such as Chrome or Firefox.

On Location - Vietnam

Pezzella, A. Thomas (2017): On Location - Vietnam.

CTSNet, Inc. https://doi.org/10.25373/ctsnet.5475670

Retrieved: 18:25, Oct 16, 2017 (GMT)

Introduction

The goal of the On Location series is to give a brief overview of the evolution of cardiac programs and voluntary cardiac surgery activities in developing countries and evolving economies. Hopefully, other individuals and organizations will share their own experience, results, and recommendations.

Background

Vietnam is a vibrant, densely-populated, small country of more than 95 million people in Southeast Asia. It embarked on the painful process of recovery in 1975 with reunification under a socialistic government, after the 1973 withdrawal of US forces from South Vietnam and the lifting of the US embargo of Vietnam in May of 1975. Over the ensuing years, Vietnam has continually developed a delicate balance between socialism and the democratic free enterprise system (Figure 1).

The present life span in Vietnam is 70.9 years for men and 76.2 years for women, and approximately 40% of the population is under 25 years old. The country has made significant strides in the political and economic sectors, but its progress has been slower in the education and healthcare sectors. GDP growth per capita averaged 6.1% in 2016 (1). The population living below the poverty line is 11.3% (1). Healthcare spending is 7.1% percent of GDP and remains socialized with progressive attempts to provide global government health insurance programs and support private insurance schemes. Fifty to 70% of healthcare spending remains “out of pocket” (2). The under-five mortality rate was 17.8 per 1,000 live births in 2013 (1). The total fertility rate (TFR) is 1.82 children born. The Health Development Index (HDI) for Vietnam is 0.683, ranked 115 of 182 countries (Low is less than 0.499; Medium 0.500-0.799; and High 0.800-899) (3). This ranking is based on life expectancy; adult literacy; primary, secondary, and tertiary gross school enrolment; and GDP per capita.

Figure 3. Shrapnel injury to right neck and chest from delayed explosion of remaining Vietnam War ordinance in the Delta region, while playing with two other friends who died at the scene.

Throughout the still evolving developments and the struggles of wars and derision, the character and culture of the Vietnamese people continues to endure and flourish (Figure 2). Unfortunately, there remains a current reminder of the previous war years (Figure 3).

Evolution of Cardiac Surgery in Vietnam

In Vietnam, the public health and curative sectors of pyramidal healthcare includes the communal, district, provincial, and national medical center levels. The efficiency and progressive flow through the system depends on geographical location, finances, bureaucracy, and the complexity of the residual double burden of communicable and noncommunicable diseases.

A brief history of cardiac surgery in Vietnam (4):

1958: The first cardiac operation was performed by Professor Ton That Tung on February 28, 1958. Through a left thoracotomy, a closed mitral commissurotomy was performed on a 30-year-old man with rheumatic mitral stenosis. Three months later, a pericardiectomy was performed on a patient with tuberculosis (TB) pericarditis via a left thoracotomy and transection of the lower sternum.

1960: Using a dilator technique, a team of Russian surgeons led by Professor Alexander Libov performed the first valvotomy of both the aortic and the mitral valves. Ligation of a patent ductus arteriosus was already routinely performed by the local surgeons.

1964: The first open heart operation using deep hypothermia was performed on an 18-year-old man with congenital pulmonic stenosis.

1965: The first open heart operation using cardiopulmonary bypass (with the aid of a Kay-Cross oxygenator) was performed in a 20-year-old woman who underwent direct suture repair of an ostium secundum atrial septal defect.

1965-1972: Several closed heart patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) procedures were performed at USA military hospitals in the south.

1972: A series of operations was performed, including procedures to correct atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), pulmonic stenosis (PS), and tetralogy of Fallot, with the aid of a Sarns pump and Travenol plastic oxygenators donated by the American Quaker Society.

1979: A French surgical team, headed by Professor LeCompte from Laennec Hospital in Paris, assisted with the first mitral valve replacement, in which an Ionescu-Shiley bioprosthesis was used. A series of nine other operations were subsequently performed.

1980-1983: Fewer than 10 open heart operations per year were performed, due to a lack of equipment, supplies, devices, trained personnel, and funding.

1989-1994: The development and growth of cardiac surgery was accelerated in 1992 with the opening of the new Carpentier Heart Institute (now the Vietnam Heart Institute) in Ho Chi Min City (HCMC, formerly Saigon) by the French surgeon Professor Alain Carpentier. Presently, over 1,000 open heart operations per year are performed, and the Vietnam Heart Institute is a major center for ongoing training of cardiac surgeons and other team members.

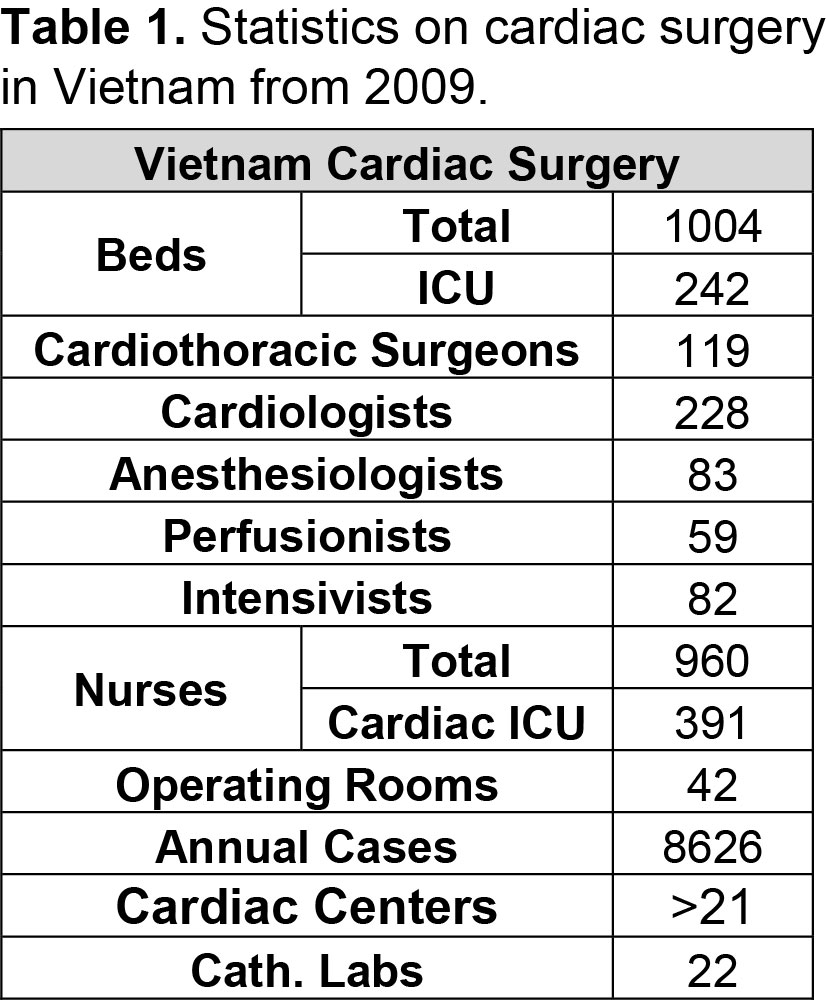

Presently, there are fewer than 25 centers (public and private) performing more than 8,000 cardiac surgery operations in Vietnam, which are done mainly in the major cities (Hanoi, Hue, Danang, and HCMC) (see Table 1 for statistics). Yet, only four centers perform more than 1,000 cases per year. Neonatal and high-risk congenital surgery is available in only seven centers. Over 100 cardiac surgeons (senior, junior, assistants) perform over 8,000 procedures annually in Vietnam. Yet the estimated prevalence or backload of patients requiring interventional, adult or pediatric cardiac surgery is 50,000-80,000. The majority of cardiac surgeons are employed by the central or local government, with a monthly salary ranging from $200 to $400 (USD). Salaries are supplemented by performing other operations or working in private initiatives. The majority of centers are government or public, though the number of private centers is increasing.

In Vietnam, more than 80% of the caseloads are valve surgery secondary to rheumatic heart disease (RHD), and congenital heart disease (CHD), especially ASD, VSD, tetralogy of Fallot, PDA, and PS. There are about 15,000 newborns per year with CHD that add to the backload. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in both groups is a significant risk factor, as well as pneumonia and failure to thrive in the pediatric group. This is a reflection of delayed presentation, incomplete assessment, incorrect evaluation, or late referral.

Rheumatic fever and children with RHD remains prevalent, but is slowly decreasing due to an aggressive government prevention program. Yet, there remains a backlog of over 5,000 adult patients that require surgical treatment of RHD. The majority of surgical RHD cases require multiple valve surgery. As noted, replacement is more common, with the Vietnam Heart Institute performing the majority of mitral valve repairs.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) accounts for 25% of the yearly mortality in Vietnam. The burden of stroke is 22% and coronary artery disease (CAD) is 7% (5). Coronary artery bypass grafting is increasingly used, and is available in all the cardiac centers, yet percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (63%) is more commonly done. Interestingly, each stent costs about $1,000 each.

At the same time, Vietnam has the challenge of communicable and non-communicable diseases. TB remains common. Annually, it is estimated that Vietnam has 17,000 TB deaths, and an estimated 180,000 people have active TB each year, with 5,000 of those cases classified as multi-drug resistant TB (6). An estimated 255,000 people in Vietnam are living with HIV, and HIV/AIDS causes 8,900 deaths per year (1).

CHD has received the most attention from voluntary international groups. The average cost for heart surgery is $1,500 - $4,500 for congenital heart disease and $2,000 - $5,000 for valve or coronary artery surgery (the average prosthetic mechanical valve costs about $1,000, the bioprosthetic valve costs between $1,500 and $2,000). The central government program now provides financial support for children less than six years of age with CHD undergoing open heart surgery. However, this program is not consistent. Not every child is totally covered, since there are varying differences in government coverage at the ward, district, provincial, and city levels (7). Out-of-pocket cost per patient ranges from $200 to $500.

The overall incidence and prevalence of CHD is growing secondary to increased objective recognition (2D screening and fetal ECHO), especially in neonates. In most of the cardiac centers, the average surgical caseloads include over 50% congenital heart disease. Neonatal congenital cardiac operations, defined as under one month old or weight below five kg, continue to increase.

Figure 4. Young talented female pediatric cardiac surgeon at Children’s Hospital # 1 (Nhi Dong #1) in HCMC.

Pediatric cardiac surgery is available at National Pediatric Institute in Hanoi, E Hospital in Hanoi, Central Hue Hospital/Heart Institute in Hue, Children's Hospital #1 (Nhi Dong #1) in HCMC, Children's Hospital #2 in HCMC, and the Vietnam Heart Institute in HCMC (Figure 4). There remains debate regarding the number and location of these neonatal cardiac surgery centers.

Because CHD presents late, secondary to delayed diagnosis or late referral, the common sequelae include failure to thrive and pulmonary hypertension. This results in increased hospital stays and frequent readmissions. However, since 2009, there has been a gradual improvement in the experience of all the pediatric cardiac team members. This has been expanded by the help of the foreign teams and individuals who have continued to support the programs.

In summary, the specific current challenges in CHD include:

- late diagnosis and referral, especially from the provincial areas, as well as an increased number of neonates requiring early or urgent surgery secondary to earlier recognition with 2D ECHO,

- inadequate infrastructure,

- need for continued upgrading training and retention of cardiac team personnel, and

- an inadequate supply of drugs, devices, and new and advanced equipment (eg, anesthesia drugs, perfusion supplies, nitric oxide, mechanical ventilators).

The effort to reduce the backlog and waiting list for surgery is hindered by the backlog of cases competing with the acute and urgent neonatal cases (7).

Major advances have occurred in recent years. Cardiac transplantation was initiated in Vietnam in 2011 at the Third Military Hospital in Hanoi, in 2011 in Hue, and at Cho Ray Hospital in 2017. The first heart assist device was implanted at the Hue Cardiac Institute in 2016. At present, there are 13 government-supported hospitals with varying levels of specific transplant capability. Several centers are now performing minimally invasive aortic and mitral valve procedures with good results. Continued foreign support will accelerate these initiatives.

Education and Training

The future and growth in the quality and quantity of cardiac surgery in Vietnam depends on the education and training of the cardiac team members, especially the cardiac surgeons. The cardiac team includes: cardiac surgeon, anesthesia, perfusion, intensivist, cardiologist, nurses (OR, ICU, Ward, Clinic), and the biomedical technician. All of them have varying levels of training and experience.

There are three approved government cardiothoracic surgery training programs in Vietnam, located in Hanoi, Hue, and HCMC, as well as the private Vietnam Heart Institute in HCMC. Yet, the majority of senior cardiac surgeons (about 20% of current cardiac surgeons in Vietnam) have received all or part of their formal and additional training abroad in France, Australia, or South Korea. The former is no longer a viable or rewarding option given the difficulties of visas, less opportunity for clinical credentialing, and less “hands on” experience. Therefore, it is incumbent on Vietnam to educate its own candidates and determine the correct annual number for the viable job opportunities.

Currently, many of the practicing cardiac surgeons have spent varying periods of time at the Vietnam Heart Institute. In addition, some have received one to three months of observational training abroad. There is consensus amongst those cardiac surgeons interviewed that the immediate or future needs of cardiac surgeons in Vietnam include further education, training, and experience. This will require bold attempts and support to develop in-country training programs.

A professional society called the Association of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery of Vietnam meets twice a year and presents a very comprehensive CME program, as well as publishing a peer-reviewed cardiothoracic surgery journal. Eighty percent of the perfusionists are doctors. Additional combined thoracic surgery training is available at Viet Duc and E Hospitals in Hanoi, Danang General Hospital, and Cho Ray hospital in HCMC.

In Vietnam, the basic educational system for the cardiac surgeon includes 12 years of primary or elementary school, followed by the six-year university bachelor of medicine degree. There is an additional alternative academic pathway of four to six years to obtain the Masters and Doctor of Medicine degree. The tuition is negligible for those who qualify for the university medical school, thus minimizing financial debt, however there is no centrally coordinated or monitored clinical residency nor graduate medical education system.

There are only three government-established, structured, “in-house” cardiac surgery training programs in Vietnam. Viet Duc Government Hospital in Hanoi has a three- to five-year program that combines general and cardiothoracic surgery. Cho Ray General Hospital in HCMC has a three-year cardiac surgery training program that also includes general thoracic surgery. The Vietnam Heart Institute in HCMC has the oldest and most organized private program for training the entire cardiac care team, including the cardiac surgeon. At present, their initial rigid French-styled system for selecting cardiac surgery residents includes a written and oral examination for the graduating medical student. This is followed by a three- to six-month observational period wherein the resident is evaluated. If selected, the aspiring resident receives three and a half additional years of formal training. Following this period, the surgeon spends three to five years as a junior staff member before being selected as senior staff or recommended as senior surgeon to another institution.

Cho Ray General Hospital Cardiac Surgery Residency Program

There is no consensus in Vietnam regarding the annual number of cardiothoracic (CT) surgeons needed to fill the available job opportunities. In July 2010, the Vina Capital Foundation sponsored a one-month survey of the active cardiac surgery centers. The goal of this project was to gain basic data that included number of staff, infrastructure, and annual caseloads. Interviews were conducted with cardiac residents and staff. A major finding was that there was no organized and approved country-wide cardiac surgery residency program. The four existing programs each had their own system that had been designed in-house. It was clear that changes were needed in the structure of CT surgery education and training. Over a one-year period, correspondence was exchanged with Cho Ray General Hospital in HCMC, the major medical teaching center in the south, to develop a model education/training program.

In collaboration with the Cho Ray Hospital training department and the NGO Hearts Around the World, a six-month project was started in July of 2012. The education and training department at Cho Ray Hospital approved a project to establish a five-year CT surgery residency program following completion of the six-year medical school program. The results of this project have been published (8).

The senior surgeons, especially those trained abroad, must be responsive, enthusiastic, and dedicated to the education and training of the younger residents. They need to be a model for the future CT surgeon, willing to transfer their experience to the next generation, as well as contributing to the development of their cardiac department. The major challenge in the Vietnam residency programs is the clinical teaching staffs’ ability and willingness to properly coach, manage, instruct, and mentor the aspiring young residents (Figure 5). Hands-on experience and gradual phased increases in resident responsibility are lacking, as they are in many of the cardiac surgery residency programs around the world.

Foreign Aid Initiatives and NGOs

As noted, a number foreign countries, NGOs, corporations, and individuals have been engaged with projects in Vietnam over the past 30 years (appendix). The major focus has been adult cardiac disease and pediatric CHD. There has been little attention given to vascular and thoracic diseases. Cho Ray Hospital in HCMC does have an active vascular and thoracic service. There has been a slow development of minimally invasive heart valve disease treatment at E Hospital in Hanoi, as well as at Cho Ray Hospital in HCMC. Several heart transplants have been performed at Viet Duc Hospital in Hanoi, Hue Heart Center in Hue, and recently at Cho Ray Hospital in HCMC. General thoracic surgery that includes treatment of cancer and TB is done in Vietnam, with TB surgery primarily performed at the TB hospitals in Hanoi and HCMC.

HCMC

Professor Alain Carpentier from Hospital Broussais in Paris, France made the greatest impact on cardiac surgery in Vietnam with the start of the Heart Institute project in HCMC in 1989. The center was established in Paris where Vietnamese cardiac care teams were trained. Teams comprised of French and Vietnamese surgeons began operating in 1992. Within several years, the program was progressively managed by the Vietnamese cardiac team. Over 1,200 cases are now performed annually under the present chief of cardiac surgery, Dr Nguyen Van Phan, who has developed an international reputation with his aggressive approach and gratifying results with complex rheumatic valve repair.

As noted, Cho Ray General Hospital in HCMC has made significant contributions in both the growth of annual operations (over 1,000) and in the training of cardiac surgeons. In cooperation with Children’s Hospital #1 (Nhi Dong #1) and the NGO Children’s Heart Link, they have developed the concept of supporting a satellite cardiac center at the provincial Kien Giang General Hospital in Rach Gia City. This hospital will serve as a model for future study and duplication in other provinces.

Vina Capital, the International Quality Improvement Collaboration (IQIC) from Boston, Massachusetts, US, and Children’s Hospital #1 have combined on a number of projects to increase the quality and quantity of CHD surgery.

Hanoi

Viet Duc University Hospital in Hanoi, the major surgical training center in the northern part of Vietnam, restarted open heart cardiac surgery in 1994. This effort was initiated with the US Committee for Scientific Cooperation with Vietnam, a humanitarian nonprofit organization that has been engaged in a variety of activities over the past 30 years, including public health and other medical projects. At their request, a cardiac surgery group from the International Children’s Heart Fund visited Hanoi in September of 1991 to assess the country's open heart surgery capability. Following that visit, a 3-year program with Viet Duc Hospital was initiated. Heart valves and miscellaneous supplies were sent in December 1991. Through February of 1992, 13 successful open heart procedures were performed there. In July of 1992, Dr Dang, then chief of cardiac surgery and anesthesiology at Viet Duc Hospital, spent two months at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center (UMMC), observing current techniques and procedures. A 20-foot container of donated equipment, devices, and supplies was sent to Hanoi in April 1994. Finally, in November 1994, a team from UMMC, including a cardiac surgeon, a perfusionist, an anesthesiologist, and a biomedical engineer, spent two weeks at Viet Duc Hospital, assisting and advising the open heart team.

Presently, over 1000 open heart operations are performed annually at Viet Duc Hospital. Professor Dang Han De, the recently retired chief of cardiac surgery at Viet Duc Hospital, did a monumental job in keeping cardiac surgery alive during the “lean years” from 1968 to 1994. Dr Le Ngoc Thanh, his successor, continued this work by implementing operations for neonatal CHD in a practical and phased way, both in terms of decreasing age and weight and increasing complexity. He has continued this work in the new government E Hospital in Hanoi. The present chief, Dr Nguyen Huu Uoc, has expanded the program to include a model training system and clinical research. With assistance from Germany, the present surgical facility was remodeled and a new center was added.

Hue

The city of Hue, the ancient capital of Vietnam, serves the central portion of Vietnam. The Hue Government/Institute of Cardiac Surgery has developed with the assistance of The Atlantic Philanthropies, East Meets West Foundation, and the Royal Children’s Hospital of Melbourne, Australia.

Summary

Major goals for the cardiac surgery community in Vietnam include increasing governmental funding for cardiac care and surgery programs and services, as well as increasing support from and cooperation with the private centers. Both the basic and more advanced surgical techniques must continue to improve, be they minimally invasive or percutaneous. Research and development initiatives—both clinical and basic—need to be established, private practice models must continue to emerge, and a country-wide graduate medical education (GME) system must be developed and coordinated jointly by the ministers of health and education.

Additional specific areas to address in Vietnam relate to infrastructure and resources, healthcare personnel needs, and development goals. These areas include increased access to and availability of critical cardiac care services, as well as continued infrastructure improvements including new construction, expansion, and remodeling. Centers must also successfully acquire new equipment, update old equipment, and ensure availability of preventive biomedical support. Specific items needed in adult and pediatric cardiac care include free ambulances services for transferring patients, ECMO devices, nitric oxide machine, echocardiographic machines, mechanical ventilators, monitors, IV pumps, specialized beds in the cardiovascular ICU, and cardiac drugs—especially PGE-1—which are not readily available in many of the hospitals.

It is critical that hospitals both increase their number of well-trained cardiac healthcare personnel and successfully retain them. Assessment of immediate and future cardiac care needs of the human resources personnel, especially cardiac surgeons, intensivists, perfusionists, nurses (OR, ICU, wards, clinic), cardiologists, anesthesiologists, and biomedical technicians is important.

An important goal is the phased development of neonatal cardiac surgery at designated centers, which must increase. Similarly, complex neonatal cardiac surgery must develop. Specialized interventions for CHD are sparingly available. This includes balloon atrial septostomy and PDA stenting, urgent cardiac surgery for newborn, and increased training and experience in pediatric cardiac surgery for complicated CHD. The latter two interventions are available in only five hospitals in Vietnam, and adequate facilities for postoperative follow-up of CHD are not available in many of the provincial hospitals (7). Finally, focused formal agreements, such as a memorandum of understanding, will be important for nurturing and supporting new or future international NGO support.

At present the growth and development of open heart surgery in Vietnam parallels the economics and politics of health care. It is hoped that Vietnamese expertise will continue to grow in a practical and realistic way, with full awareness of the high cost and complexity of the endeavor. Cardiac surgery is an expensive but effective intervention. As their economy improves, this surgery will increasingly benefit the Vietnamese people. The author’s hope is that other individuals and groups will contribute to this narrative and share their thoughts, experiences, and recommendations.

References

- Central Intelligence Agency, United States of America. World Fact Book, East & Southeast Asia: Vietnam. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/vm.html. Updated September 27, 2017. Last accessed October 5, 2017.

- Van Minh H, Kim Phuong NT, Saksena P, James CD, Xu K. Financial burden of household out-of pocket health expenditure in Viet Nam: findings from the National Living Standard Survey 2002-2010. Soc Sci Med. 2013;96:258-263.

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Reports: Viet Nam. http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/VNM. Last accessed October 5, 2017.

- Pezzella AT. Introduction to the reports from Vietnam. Texas Heart Inst J. 1995;22(4):317-319.

- Nguyen HL, Nguyen QN, Ha DA, Phan DT, Nguyen NH, Goldberg RJ. Prevalence of comorbidities and their impact on hospital management and short-term outcomes in Vietnamese patients hospitalized with a first acute myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e108998.

- U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Vietnam. News & Events: New Treatment Brings Hope to Drug-resistant Tuberculosis Patients in Vietnam. https://vn.usembassy.gov/new-treatment-brings-hope-to-drug-resistant-tuberculosis-patients-in-vietnam/. Updated November 25, 2015. Last accessed October 11, 2017.

- Phuc VM, Tin do N, Giang do TC. Challenges in the management of congenital heart disease in Vietnam: A single center experience. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2015;8(1):44-46.

- Pezzella AT. Model 5 Year Cardiothoracic Surgery Residency Program In Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Afr Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;9:7-16.

Appendix

NGOs with past or continuing projects in Vietnam

The Atlantic Philanthropies: www.atlanticphilanthropies.org

East Meets West Foundation: www.eastmeetswest.org

Vina Capital Foundation: www.heartbeatvietnam.org

International Children’s Heart Fund: www.ichfund.org

International Children’s Heart Foundation: www.ichf.org

Children’s Heart Link: www.childrensheartlink.org

CardioStart International: www.cardiostart.com

Hearts Around the World: www.hearts-aroundtheworld.org

Royal Children’s Hospital of Melbourne, Australia: http://www.wilmoth.com.au/publications/RCH%20International%20Brochure.pdf

The Korea Heart Foundation: http://new.heart.or.kr/english/2012/work06.php

Countries with past and present volunteer relationships and projects in Vietnam

Japan, South Korea, Singapore, New Zealand, China, Taiwan, Canada, Malaysia, USA, France, Germany, Italy, Thailand, Ireland, Switzerland, Russia, Australia.

Selected Individuals

Prof Shunji Sanno, Pediatric Cardiac Surgeon, Japan

Dr Casey Culbertson, Intensivist, USA

Robin King Austin, Director of Vina Capital Foundation

Robert Jarrett, Director of Hearts Around the World-USA

Dr J. Mark Redmond, Ireland: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Mark_Redmond

Dr Sriram Shankar, Pediatric Cardiac Surgeon, Singapore

Dr William Casey, Anesthesiologist/Intensivist: http://www.apagbi.org.uk/sites/default/files/imagecache/Casey%2C%20William%20-%20Vietnam.pd

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Dr Ha Nguyen Hoang for recent updates in cardiac surgery.