ALERT!

This site is not optimized for Internet Explorer 8 (or older).

Please upgrade to a newer version of Internet Explorer or use an alternate browser such as Chrome or Firefox.

Undressing the “Full Metal Jacket”—A Case Report of Coronary Stentectomy

Vinholo TF, P. Dolan D, Harloff M, Aranki S. Undressing the “Full Metal Jacket”—A Case Report of Coronary Stentectomy. November 2024. doi:10.25373/ctsnet.27846984

Despite advancements in drug-eluting stents, in-stent restenosis (ISR) remains a challenge for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), resulting in high rates of recurrence despite various interventions. Although percutaneous approaches, such as balloon angioplasty, rotational atherectomy, and additional stenting, have been attempted to address ISR, recurrence rates remain high. ISR cases constitute 10 percent of all PCIs (1) and pose a significant modern-day challenge. While CABG has shown better outcomes for ISR patients (2), revascularization in this context is complex.

Objective

Multiple stents within the same artery may still lead to ischemia, by obstructing septal perforators and diagonal branches. This video describes an approach to tackling ISR through coronary stentectomy.

Case Report

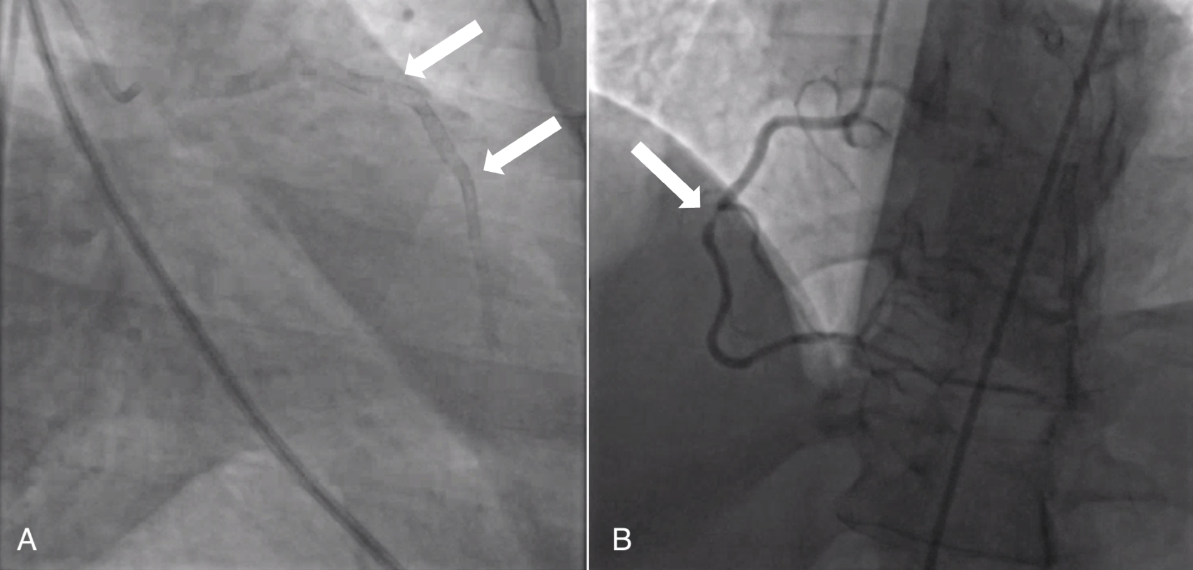

The patient was a 54-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and significant coronary artery disease, who had undergone multiple percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) and presented with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. A coronary angiography revealed in-stent restenosis (ISR) in eight drug eluting stents throughout the entire left anterior descending artery (LAD) (figure 1A). In addition, the right coronary artery (RCA) was 90-99 percent stenosed and the left circumflex (LCX) artery was diseased (figure 1B). An echocardiography showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 45 percent.

Figure 1A: Coronary angiography depicting (A) stents throughout the entirety of the LAD (white arrows)

Figure 1B: 90-99 percent RCA occlusion (white arrow)

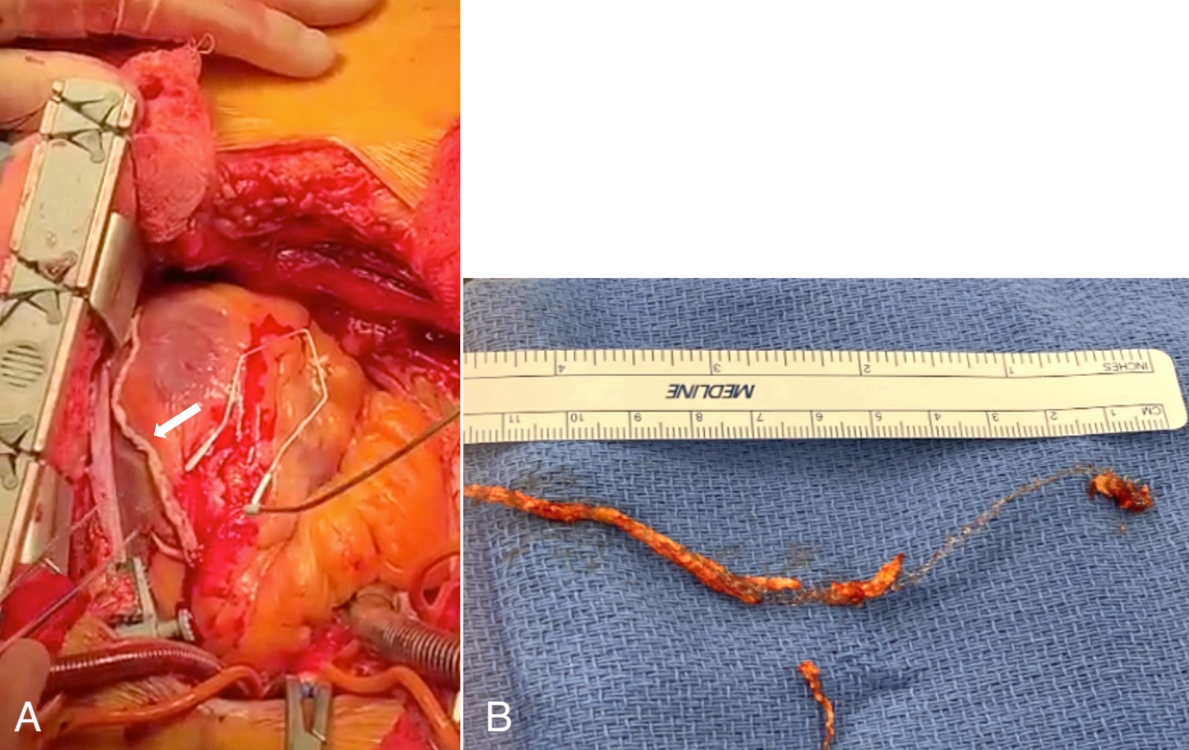

Cardiac surgery was consulted, and the patient was brought to the operating room for coronary bypass grafting (CABG). The following conduits were chosen: pedicled left internal mammary artery (LIMA), left radial artery, and saphenous vein graft. The patient underwent central cannulation with ascending aorta arterial cannulation and right atrial venous cannulation. The left radial artery was anastomosed to the RCA, and the vein graft was sequentially applied to the ramus branch and to the posterior left ventricular branch of the LCX artery. The LAD was then unroofed entirely and all stents were carefully removed. The stents were encased in a fibrous neointima, which caused obstruction of the diagonal and septal branches (figures 2A, 2B).

Figure 2 A: LAD stents encased in a fibrous neointima (white arrow)

Figure 2B: Extracted LAD stent

Endarterectomy of the second diagonal branch was then performed through the LAD arteriotomy. Retrograde cardioplegia was administered to flush and clear debris; brisk bleeding was seen in the septal perforators. The distal portion of the LAD arteriotomy was patched with a radial artery segment using continuous 8-0 polypropylene suture. The LIMA was anastomosed to the proximal end of the arteriotomy with the free edge of the LIMA sutured to the free edge of the radial artery patch. The patient was given half of the calculated dose of protamine and was separated from bypass without complication.

A cangrelor infusion (0.75 mcg/kg/min) was started before transfer to the intensive care unit. Upon arrival, 325 mg of aspirin was provided to the patient, and a non-titratable heparin infusion (500 units per hour) began once the chest tube output was under 50 mL/hour for two consecutive hours. On postoperative day two, the ticagrelor was loaded to 180 mg, followed by a transition to 90 mg twice daily 12 hours later. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was discharged to rehab on postoperative day nine.

Discussion

As demonstrated by the authors’ experience; coronary endarterectomy is a well-established method for coronary reconstruction (3). However, in certain cases, stent removal in addition to endarterectomy becomes necessary—a meticulous and complex process. Despite limited literature detailing stentectomy cases (3–5), the authors believe it is imperative to share this case report illustrating intraoperative techniques and postoperative care specifics.

A critical consideration during these procedures is the presence of multiple stents within the same artery. This presents various challenges, such as identifying a target for anastomosis and, more significantly, the potential risk of ischemia due to stent obstruction of septal perforators and diagonal branches, particularly when located in the LAD. A meticulous dissection during stentectomy mirroring the careful approach required in endarterectomy alone is necessary to prevent stent disruption and ensure complete extraction.

The extensive reconstruction involving the LAD artery inevitably leads to prolonged cross-clamp and cardiopulmonary bypass times. The use of retrograde cardioplegia not only provides myocardial protection, but also mechanically flushes and clears any debris that may have embolized distally. Visual confirmation of brisk bleeding from perforators, indicating clearance of all debris, is crucial.

To prevent thrombosis, a cautious approach to heparin reversal was adopted by administering only half of the calculated total protamine reversal dose. Post-procedural targeted therapy, including heparin, ticagrelor, and aspirin administration, is essential to prevent thrombosis and occlusion at the stentectomy site. Strict adherence to a postoperative antiplatelet therapy protocol is imperative for preventing platelet activation, aggregation, thrombus formation, and to maintain graft patency.

Editor's Note

Be sure to watch CABG With a Long LAD Endarterectomy by Dr. Vince Gaudiani. In this clinical video, Dr. Vince Gaudiani demonstrates a long LAD endarterectomy with vein valve removal, calcium clearance, and LIMA to vein patch. The techniques shown in this video and Dr. Gaudiani's present an interesting contrast that surgeons can review to improve routine long segment endarterectomy.

References

- Moussa ID, Mohananey D, Saucedo J, et al. Trends and Outcomes of Restenosis After Coronary Stent Implantation in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(13):1521-1531.

- Moustapha A, Assali AR, Sdringola S, et al. Percutaneous and surgical interventions for in-stent restenosis: long-term outcomes and effect of diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(7):1877-1882.

- Myers PO, Tabata M, Shekar PS, Couper GS, Khalpey ZI, Aranki SF. Extensive endarterectomy and reconstruction of the left anterior descending artery: early and late outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(6):1336-1340.

- Nishigawa K, Fukui T, Takanashi S. Off-pump coronary endarterectomy with stent removal for in-stent restenosis in the left anterior descending artery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015;21(5):594-597.

- Fukui T, Takanashi S, Hosoda Y. Coronary endarterectomy and stent removal in patients with in-stent restenosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(2):558-563; discussion 563.

Disclaimer

The information and views presented on CTSNet.org represent the views of the authors and contributors of the material and not of CTSNet. Please review our full disclaimer page here.